priviledge and what it really takes to get into harvard

In 1642, Harvard Higher held its first commencement. The graduating class consisted of just nine students. It goes without saying that all were white, Christian, and male.

Harvard reinforced the exclusive nature of college pedagogy by not ranking its graduates past their grades or alphabetically. Instead, these elite men crossed the phase "according to the rank their families held in lodge."

For the adjacent 121 years, Harvard connected to allocate its graduates by their family unit condition.

Higher instruction began every bit a privileged establishment, designed to accelerate a sure kind of student and exclude others. Although generations have fought to broaden access to colleges and universities, privilege continues to shape higher learning in the 21st century.

Higher and the "Poor Boy"

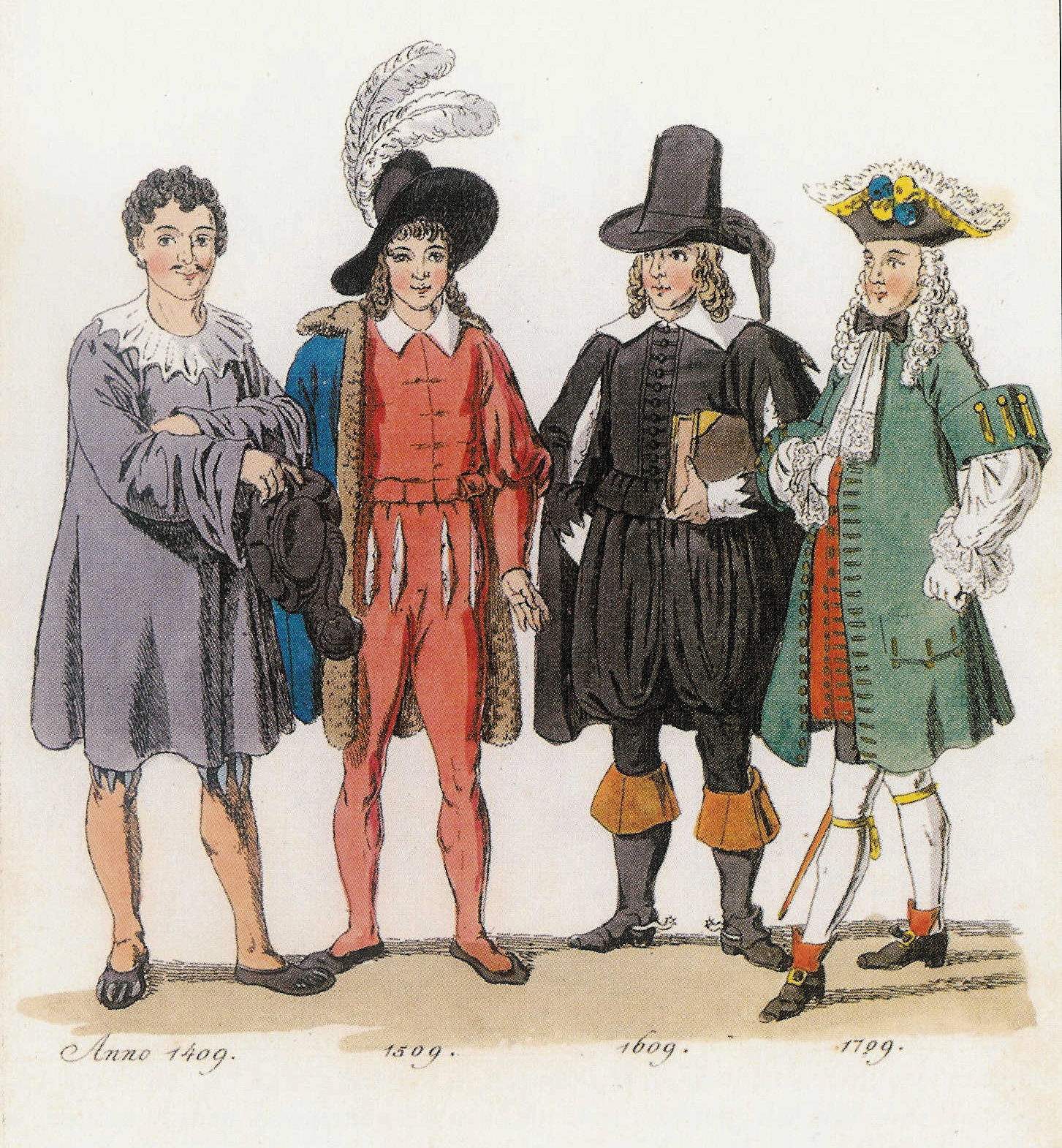

Starting in the Middle Ages, Europe'southward colleges and universities were meant to train the sons of wealthy men for careers in constabulary, medicine, and the church. Higher education had little to offer the sons of cobblers and farmers, who learned the crafts from their fathers. As a effect, higher education remained almost inaccessible to all except wealthy sons for generations.

Prior to the 20th century, the loftier toll of higher educational activity was not due to tuition; rather, only the wealthy had the luxury of spending years out of the workforce to pursue an instruction.

When influential English physicist Isaac Newton wanted to attend the Academy of Cambridge in the 17th century, his farmer stepfather couldn't human foot the bill for his living expenses, leading Newton to pay his way through school past becoming a servant for wealthy students.

Meanwhile, in the American colonies, Harvard devised a similar solution. In 1653, Harvard student Zachary Bridgen paid his way by ringing the bell and waiting on the tables of his fellow students.

Poor students attending elite higher education institutions were oftentimes considered 2nd-form citizens.

Fifty-fifty though students like Newton and Bridgen gained access to elite institutions, they were forced into a 2nd-form status simply because of their poverty.

By the early 20th century, many colleges and universities began administering financial aid programs to expand access to college instruction. But these new aid systems raised complicated questions well-nigh which students merited support.

In a 1933 essay for The Atlantic, Russell Sharpe wrestled with what he titled "College and the Poor Male child." Sharpe lamented a recently appear policy at Yale Academy, which stated that the school would only admit as many "financially needy students" equally its current aid level could support. Such policies, he feared, would punish deserving students without the ways to pay for higher.

Working students was a relatively new miracle back in Sharpe'south day, when only ane in 3 college students sought office-time or summer piece of work. Nowadays, 70% of full-time students rest school with a job.

A persistent myth identified by Sharpe survives today — the thought that working while in school will "rob college of much of its value" and even "exert a harmful influence upon the individual." Yet this myth rests on the assumption that economic privilege is the norm in higher and the less well off are a deviation from that norm.

Then what was Sharpe'due south solution to the trouble of college and the poor male child? Acknowledge fewer students. By making college more exclusive, he reasoned, institutions could fund academically excelling, impoverished students.

Russell Sharpe believed that making colleges more selective would allow them to ameliorate fund impoverished students.

"Those who are disturbed by such a prospect should remember," he argued, "that the poor boy of real ability would withal be able to proceeds entrance under an intelligent system of limitation."

Ironically, Sharpe'southward proposal reinforced the privileged nature of higher pedagogy. Fifty-fifty equally 20th-century colleges and universities reimagined their pupil bodies, the "standard" student remained white, male, and wealthy.

The 19th-Century Battle for College Access

For centuries, higher remained almost exclusively the domain of white men. But in the 19th century, those excluded from higher learning battled furiously for access to the institution. Not surprisingly, colleges — and college students — fought back.

When Sophia Jex-Blake applied to Harvard in the 1860s, the college rejected her application using the rationale that there was "no provision for the teaching of women in any department of this university."

Jex-Blake eventually gained admission to Edinburgh University to study medicine, where she and six other female students — known as the "Edinburgh Seven" — were forced to pay higher fees than the male students. In addition, the university let professors refuse to teach women, forcing Jex-Blake and the other female person students to arrange their own lectures with supportive faculty members.

In 1870, a mob of hundreds surrounded the women equally they took an beefcake examination. Now known as the Surgeon's Hall riot, male students attempted to force the women out of the academy, fifty-fifty shoving a sheep into the exam room. The professor proctoring the exam reportedly quipped, "The sheep can stay, information technology is clearly more intelligent than those out in that location."

Ultimately, the university refused to grant degrees to any of the seven women. Institutional barriers, such as universities denying admission to women or allowing kinesthesia to pass up to teach female students, created nearly insurmountable barriers to college instruction, which were designed to protect the privilege of students who saw college as their domain and theirs solitary.

Like barriers excluded Black people from U.Southward. colleges. In 1850, when Harvard Medical School admitted 3 Black students, white students spoke out against the conclusion then forcefully that Harvard withdrew its admission offers.

Institutional barriers have historically prevented women and Blackness citizens from attending higher and earning their degrees.

What'due south more, many states legally banned Black teaching. The Virginia Code of 1819 outlawed didactics enslaved people to read or write. Many colleges and universities maintained a policy of refusing to admit Black applicants. Every bit a result of existence shut out of the education system, Black Americans established historically Black colleges and universities, more commonly known every bit HBCUs.

The battle for access continued well into the 20th century. Accept again, for example, Sharpe'south 1933 article, which confidently declared, "It has been a part of the democratic creed of many Americans that every female parent's son is born with an inalienable right to a available'south degree." Sharpe assumed, as did then many others, that by definition college students were men.

The 20th century introduced a new method to maintain privilege in higher education: the fiction of a purely meritocratic admissions organization.

Debunking the Myth of Meritocracy

Though colleges had grown more than diverse by this century, many institutions connected to fight for a more exclusive atmosphere. In their fight, they used a new weapon: meritocracy.

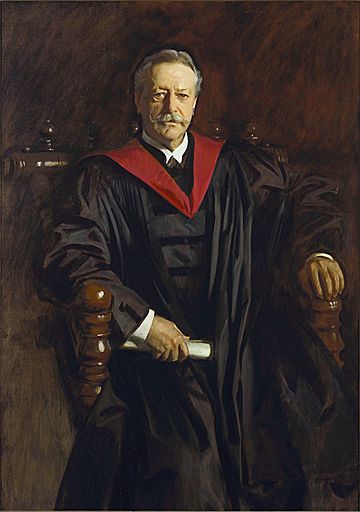

As Harvard increased its student diversity, President A. Lawrence Lowell, who ran the university from 1909-1933, suggested a quota organisation. Specifically, Lowell wanted to keep out Jewish students, arguing that besides many of them would bulldoze abroad Christians. Lowell too banned Harvard'due south Black students from the dormitories and dining halls.

In the stop, Harvard didn't prefer an overt quota arrangement — it inverse its application procedure. Rather than simply using examination scores to admit freshmen, the schoolhouse prioritized factors like family unit background and the nebulous concept of "fit." Harvard claimed that the new arroyo would create a more inclusive schoolhouse, describing it as a "policy of equal opportunity regardless of race and religion."

In practise, the admissions organization intentionally favored already privileged students — i.e., the wealthy white men who would make upwardly the majority of Harvard's alumni for centuries. New factors, such as legacy admissions and athletic recruitment, made information technology easier than ever to justify admitting the aforementioned type of students.

While publicly arguing that anyone of merit could and would rise to the top, colleges privately reinforced exclusionary policies.

In the words of Yale law professor Daniel Markovits, "American meritocracy [has] become precisely what it was invented to combat: a machinery for the dynastic manual of wealth and privilege across generations."

Nether the arrangement of admitting students by merit, rejected students constitute a new scapegoat: beneficiaries of programs designed to expand admission to higher education.

Though colleges claimed to base of operations admissions on merit, most privately reinforced exclusionary practices.

According to NAACP Legal Defence and Educational Fund senior counsel Rachel Kleinman, opposition to affirmative activeness, which began in the 1960s, stems from "this fearfulness of white people that their privilege is existence taken abroad from them and given to somebody else who they see as less deserving."

In exercise, admissions policies at selective schools however favor wealthy, white, male person students.

Privilege in Higher Education in 2020

In 2020, colleges and universities actively promote diversity in their student bodies. Multifariousness and inclusion programs work to recruit and retain students of color and other underrepresented groups — even so many policies still favor privileged students.

For instance, almost forty% of institutional financial help goes to students without demonstrated fiscal demand. At some of the most exclusive colleges, the student torso contains more students from the peak ane% than the bottom sixty%.

Educational systems created to privilege one group over others resist change. A recent study from Georgetown University's Centre on Education and the Workforce concluded that the American higher education system perpetuates white privilege.

The most selective colleges still enroll predominantly white students, while students of colour largely attend less selective public institutions. This systematic exclusion affects the graduation rate and lifelong earning potential of students of color.

Even today, at some of the most sectional colleges, there are more students from the top 1% than there are the lesser sixty%.

The rising price of tuition has become another barrier that privileges wealthy students. Although the cost of college more than than doubled between 1974 and 2012, the maximum Pell Grant, which was designed to support low-income students, remained relatively stagnant.

In practise, the ascent cost of college and the lack of financial support excludes students who accept been fighting for centuries to admission higher education.

Today, the admissions procedure still offers hidden, backdoor admission to privileged students. In 2019, teaching researchers argued that "the most damaging myth in American higher educational activity is that college admissions is nigh merit." In reality, privileged students heave their chances through test-prep coaching, legacy admissions, and athletic admissions.

Consider last year'due south college admissions scandal. While celebrities similar Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman broke the law to secure spots for their children, thousands of other wealthy families lean on legal donations or legacy status to reinforce their privilege.

Similarly, admissions preferences for athletes largely benefit white men at elite institutions, where playing lacrosse or h2o polo can secure students a spot in the incoming class. A 2002 study constitute that athletes fared meliorate during admissions than even legacy students. Athletes got nigh double the boost of legacy students and received admission offers at almost three times the rate of students of color.

In an article for Vox, Jason England, former dean of admissions at an elite liberal arts institution, argued, "I don't believe you can reform higher admissions from the inside. The game favors the wealthy and powerful, and that's an extension of our society."

But privilege doesn't stop after the gauntlet of the admissions process. In fact, over the by 45 years, the higher graduation gap betwixt rich and poor students has widened. In 2013, 99% of wealthy students finished their bachelor's degree, while only around 20% of students in the lowest income group earned theirs. Compared with 1970, this gap is much wider — and much more than discouraging.

Colleges and universities committed to multifariousness and inclusion still confront a daunting challenge today: undoing centuries of policies designed to privilege a certain kind of student.

knetespromfonston.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.bestcolleges.com/news/analysis/2020/07/17/history-privilege-higher-education/

0 Response to "priviledge and what it really takes to get into harvard"

Post a Comment